How can Simon Singh donate to Hacked Off?

DANIEL Boffey tells readers of The Observer, names of wealthy donors to the Hacked Off campaign.

He lists a few of the names: Arpad Busson, Guy Chambers and Simon Singh. Singh donated £1000. He said:

“It is about getting the balance right between free speech and a responsible press.”

Sections of the press behaved badly. They were dealt with by the law. Free Speech has no buts. It is either free or it isn’t. You can’t get to the truth if you’re shackled.

Singh is an interesting donor. He once took on the libel system and won. In 2008, Singh wrote an article in the Guardian in which he said that a chiropractor “happily promotes bogus treatments”. The British Chiropractic Association was upset. Singh said “alternative therapists who offer treatments unsupported by reasonable evidence are deluded rather than deliberately dishonest”. But the couts said he’d done wrong. He was being sued for expressing an opinion.

Under the headline “Simon Singh: Let us now praise a bloody-minded hero”, Nick Cohen wrote:

I don’t normally campaign. I’m not a joiner or a natural committee man. But the state of free speech in England pushed me into despair, and three years ago I started to do what little I could for the campaign for libel reform.

…Parliament reformed the law. Many people can claim credit for forcing change through. Lord Lester, who more than anyone else wrote the legislation, and Index on Censorship, English Pen and Sense About Science, who ran a model campaign. But Simon Singh deserves the most praise. His determination to fight an unjust law made reform possible.

Cohen covered what happened in You Can’t Read This Book: Censorship in an Age of Freedom.

A few months later, the British Chiropractic Association held National Chiropractic Awareness Week. Singh noted that it offered its members’ services to the anxious parents of sick children, and wrote an article for the Guardian, ‘Beware the Spinal Trap’. He began by saying that readers would be surprised to learn that the therapy was the creation of a deranged man who thought that displaced vertebrae caused virtually all diseases. The British Chiropractic Association followed suit by claiming that its members could treat children with colic, sleeping and feeding problems, frequent ear infections, asthma and prolonged crying.

There was ‘not a jot of evidence’ that these treatments worked, said Singh. ‘This organisation is the respectable face of the chiropractic profession and yet it happily promotes bogus treatments.’ He went on to explain that he could label the treatment as ‘bogus’ because Ernst had examined seventy trials exploring the benefits of chiropractic therapy in conditions unrelated to the back, and found no evidence to suggest that chiropractors could treat them.

…

The chiropractors did not sue the Guardian, but went for Singh personally, hoping that the threat of financial ruin would force him to grovel. The Guardian withdrew his article from their website, thus lessening any ‘offence’ caused, and offered the chiropractors the right of reply, so they could tell their side of the story and convince readers by argument rather than by threats that Singh was in the wrong.

The chiropractors carried on suing Singh, and demanded that he pay them damages and apologise…. At a preliminary hearing to determine the ‘meaning’ of Singh’s article, the judiciary soon showed why English law was feared and despised across the free world. Determined to draw him into the law’s clutches, the judge [Mr Justice Eady] put the worst possible construction on Singh’s words.

He ruled that because Singh had said ‘there is not a jot of evidence’ that chiropractic therapists could cure colic, sleeping and feeding problems, frequent ear infections, asthma and prolonged crying, the courts would at enormous expense see if they could find one piece of evidence, however small, to support the chiropractors. Maybe if a child stood up in court and breathlessly announced that a chiropractor had cured her, that would be a jot. Maybe if the judge could find a smidgeon of doubt in one of the studies, Singh would have to pay for a phrase that may have been ever so slightly inaccurate.

If Singh could prove that no such doubt existed, he would still not be free of the law…

After hearing the judge’s ruling, Singh’s friends, his lawyers and everyone else who had his best interests at heart advised him to get out of the madhouse of the law while he still could. He had already risked £100,000 of his own money. If he fought the case, it would obsess his every waking moment for a year, possibly longer, and he could lose ten times that amount if the verdict went against him. Even if he won, he would still lose, because another peculiarity of the English law is that the victor cannot recoup his full costs. It was as if the judiciary had put Singh in a devil’s version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire?

Singh refused to apologise. He stood by his words. It cost him £200,000 “just to define the meaning of a few words”. He said in 2010:

“After two years of battling in this libel case, at last we’ve got a good decision. So instead of battling uphill we’re fighting with the wind behind us. The Court of Appeal’s made a very wise decision, but it just shouldn’t be so horrendously expensive for a journalist or an academic journal or a scientist to defend what they mean. That’s why people back off from saying what they really mean.”

Freedom of speech is just that…

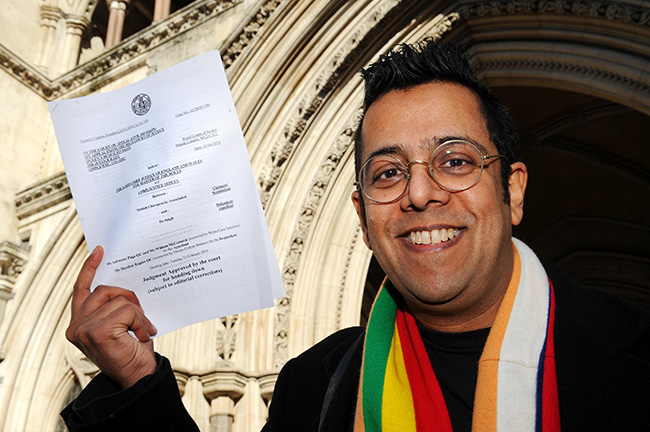

Photo: Science writer Simon Singh smiles outside the High Court, London, after he won his Court of Appeal battle for the right to rely on the defence of fair comment in a libel action. Thursday April 1, 2010.

Posted: 12th, May 2013 | In: Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink