False rape: the Scottsboro Boys become the model for UVA and campus crimes against men

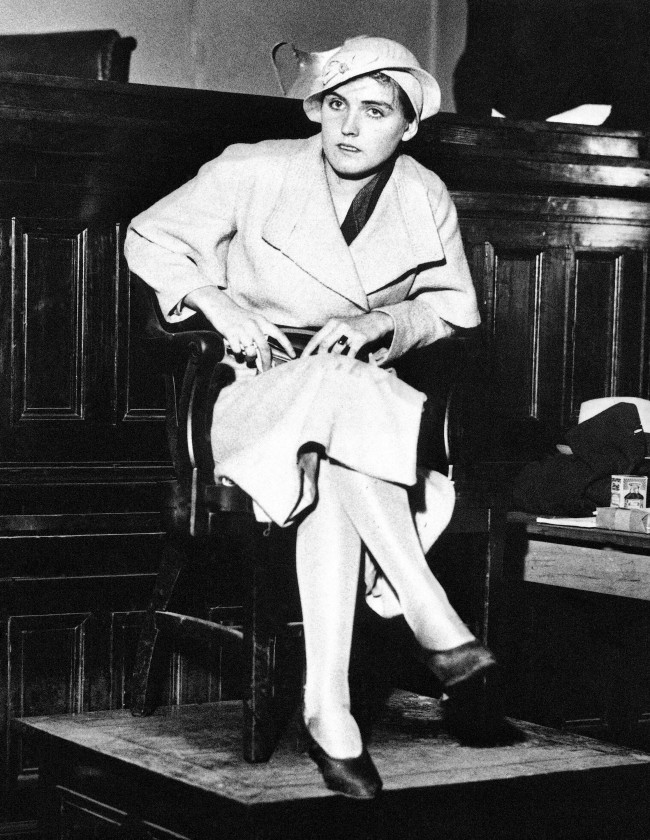

In this April 7, 1933 file photo, Ruby Bates sits in the witness stand in a courtroom in Decatur, Ala. Saying that Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick had urged her to tell the truth, Bates denied that the nine black teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Boys, had assaulted her and her companion Victoria Price.

Remember the Scottsbroro Boys? They were the nine Afro-American men tried and jailed for the rape of two white women in 1930s Alabama. The men – all of them – were innocent.

The State made the people fit the cime.

Today, so-called lad culture is being used to portray men on the street and on university campuses as rapists-in-waiting. We live in more equal age: whites and black men are all as guilty.

Professor Dan Carter first published his book on the Scottsboro Boys trials as long ago as 1969. He wrote:

“One day in the spring of 1931 a group of hobos, black and white, were travelling on a train in north Alabama. A fight broke out and the train had to be stopped near the town of Scottsboro. Nine young black men – the youngest was 13 – were arrested.

“But then the Deputy Sheriff realised two of the white hobos were in fact women. The young women worried they might be accused of prostitution, so they accused the black boys of having raped them.

“I think anyone today who studied the evidence would conclude no rapes occurred. In any case, what happened after March 1931 took on an astonishing life of its own. What happened on the train was just a part of the story.”

Racism, bigotry and ignoring truth ruined lives.

Two of the hobos wer women.

“The deputy sheriff realised two of the white hobos were in fact women,” historian Dan Carter told the BBC in October. “The young women worried they might be accused of prostitution, so they accused the black boys of having raped them.

“I think anyone today who studied the evidence would conclude no rapes occurred.”

Who needs evidence when you have agenda to drive?

At the first of numerous trials, eight of the nine received death sentences and some of them spent long periods on Death Row. That ultimately no one was executed was in part the doing of the Communist Party USA.

The communists paid for the services of celebrated attorney Samuel Leibowitz to defend the Boys. The involvement of political radicals infuriated Alabamans – some of whom didn’t much enjoy being lectured by a Jewish lawyer from New York.

But Dan Carter says the party’s money and organising abilities proved crucial. “Without them, some of the Scottsboro Boys would surely have gone to the electric chair.”

…

The last of the nine men walked free in 1950, almost two decades after the original charges.

And:

Five of the boys’ convictions were overturned, and a sixth was pardoned in 1976.

For the innocent, justice once remarkably swift and sure is slow.

Jonah Goldberg writes:

Nine males were accused of being part of a heinous rape. The alleged injustice fomented a mob mentality. An enraged community wanted to skip any talk of a serious investigation, never mind a trial, and go straight to the punishment.

I’m not talking about the now-discredited allegations against fraternity members at the University of Virginia, but of the legendary case of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American teenagers falsely accused of rape in Alabama in 1931. Despite testimony from one of the women that she had made up the whole thing, the Scottsboro Boys were convicted in trial after trial. All served time either in jail or prison.

Scottsboro is a landmark case in the history of the civil rights movement and the American justice system. Sadly, it was hardly an outlier. There’s a long, tragic history of African American men being wrongly accused and convicted of rape. The most notorious recent example is the 1989 case of the Central Park Five in which four African American teens and one Latino were wrongly accused and convicted of brutally raping a white woman in New York.

Clearly, the injustices involved in these cases are far greater than what transpired at UVA. No one at the Psi Kappa Phi fraternity faced the death penalty or went to jail. But the lessons learned and principles involved are timeless and universal; everyone deserves the presumption of innocence.

Apparently, Zerlina Maxwell disagrees. She writes in the Washington Post: “We should believe, as a matter of default, what an accuser says. Ultimately, the costs of wrongly disbelieving a survivor far outweigh the costs of calling someone a rapist.”

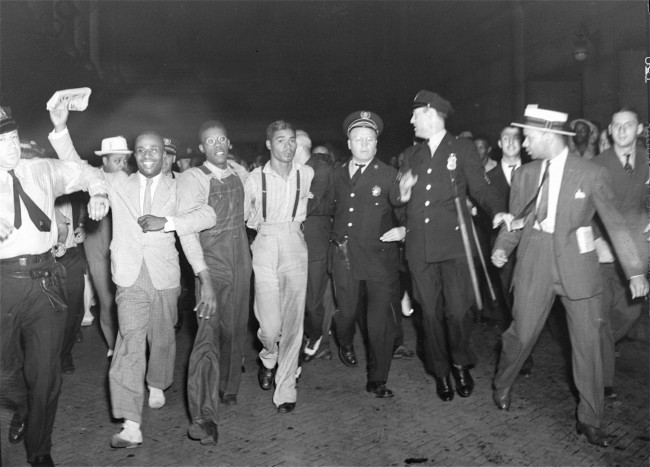

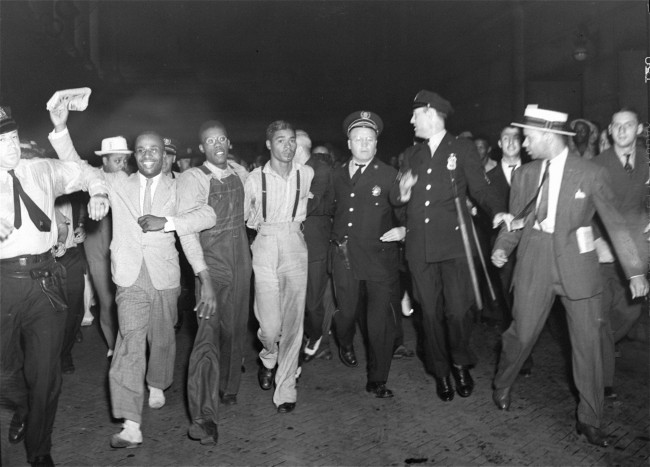

A free-for-all as officers broke up an attempt to picket the Capitol grounds in Washington on Nov. 7, 1932, by a group demanding freedom for the seven African Americans sentenced to death in Scottsboro, Ala., whose case was before the U.S. Supreme Court. Police and plainclothesmen charged the group with swinging nightsticks when they refused to disperse. One policeman was badly beaten and several arrests were made. (AP Photo)

This March 31, 1933 file photo shows some of the 12 men of Morgan County, Decatur, Ala. chosen for the jury in the retrial of Heywood Patterson, one of the nine African American teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Boys, convicted of attacking two white girls who were riding on a freight train. (AP Photo)

In this April 3, 1933 file photo, Judge James E. Horton leans over to listening to the testimony of Dr. R. R. Bridges, a Scottsboro, Ala. physician, in the Decatur, Ala. courtroom for the first of the retrials of eight of the nine Scottsboro black youths previously condemned to death for attacks on two white girls, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates. He said that he had found only superficial bruises and scratches when he examined Mrs. Price shortly after she was alleged to have been attacked aboard a train en route to Chattanooga. (AP Photo)

Here is shown a part of the crowd of 10,000 persons who jammed the courthouse square in the little town of Scottsboro, Alabama, April 6, 1933, on the opening of the trials of nine black youths accused of attacking two white girls near Sevenson, Ala., March 24, 1931. National Guardsmen with fixed bayonets patrolled the courthouse grounds, and women and minors were barred from the courtroom. The state asked for the death penalty for the first two defendants to be placed on trial. The other seven will be tried later. The nine were identified by the two girls as the ones who boarded the freight car in which they and seven white youths were riding, forced five of the white youths from the train, knocked the other two unconscious and attacked the girls.

Residents gather in Harlem, New York City, April 9, 1933, to read a placard protesting against the decision of a jury in the trial of Haywood Patterson, one of the nine Scottsboro Boys to be indicted, at Decatur, Ala. Patterson was found guilty of assault against two white girls near Scottsboro, Ala. about two years ago. (AP Photo)

These are the twelve Morgan Country Alabama men, chosen to weigh the evidence in the trial of Heywood Patterson, 19-year-old and first of seven to face re-trial in the Scottsboro attack case. The jury is shown at Decatur, Ala., April, 2,1933 where the case is being tried. (AP Photo). Date: 02/04/1933

More than 1,200 braved disagreeable weather to attend a rally in Union Square, New York City, December 9, 1933, on behalf of the nine Scottsboro boys. The meeting was arranged by the International Labor Defense and was backed by the Communist Party. The marchers carried banners and a sign with the image of a lynching, and the legend “Alabama – The land of the tree and the home of the grave.”

In this May 8, 1933 file photo, a long line of predominately African-American marchers parade past the White House in Washington to present a petition to President Roosevelt asking intervention to free the youths convicted in the Scottsboro, Ala., attack case. (AP Photo)

Ruby Bates, Alabama mill girl who caused a sensation in the last Scottsboro Trial by reversing her previous testimony that she had been assaulted by the Black defendants, leads a parade of several hundred persons through the Washington, D.C. streets to the White house, to present her petition for the liberation of the ” Scottsboro Boys. ” Ruby is the woman in the light coat in the center. ( AP Photo)

n this April 6, 1933 file photo, four of the Scottsboro Boys prisoners are escorted by heavily-armed guards into the Decatur, Ala., courtroom. Now that the Alabama Legislature is allowing posthumous pardons for the Scottsboro Boys, the nine African-American youths wrongfully convicted of raping two caucasian women more than 80 years ago, there is still much work to be done before their names are officially cleared. (AP Photo/File)

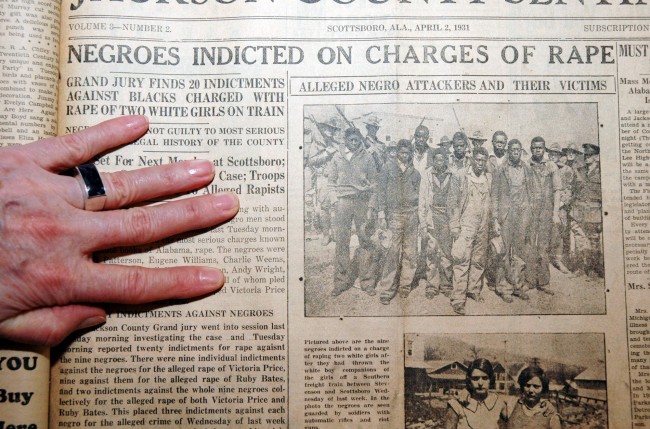

This Feb. 10, 2010 photo taken in Scottsboro, Ala., shows the Jackson County (Ala.) Sentinel from April 2, 1931, when nine young black men called “The Scottsboro Boys” were arrested on charges of raping two white women. The charges were later revealed as a sham, and the case gained notice worldwide. A new museum documenting the case has opened in Scottsboro. Only one of the nine Scottsboro Boys was formally pardoned by Alabama before dying. State officials would like to clear the names of the other eight, but figuring out how to rewrite history after 81 years is proving difficult. (AP Photo/Jay Reeves)

J. Howard Haring, left , and J. Vreeland Haring, Sr., wait to take the stand, as handwriting experts for the state, in the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, accused Kidnap-killer of the Lindbergh baby, in Flemington, N.J., Jan. 14, 1935. The Harings have appeared as handwriting experts in many celebrated cases, among them the Scottsboro case, the Starr Faithfull disappearance case, and the Hall-Mills murder case. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.9977295

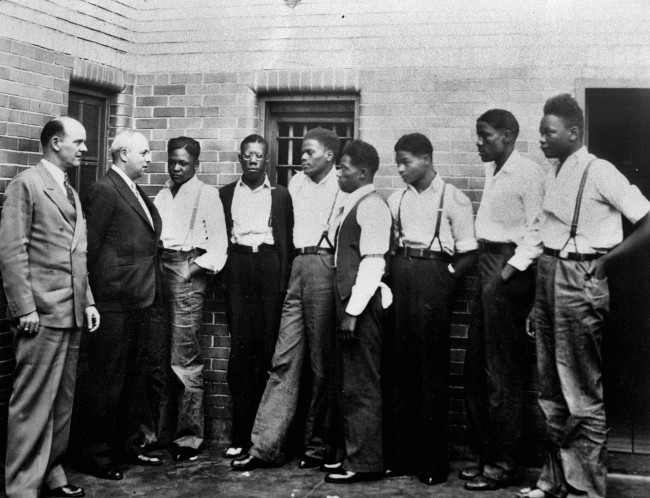

In this May 1, 1935 file photo, attorney Samuel Leibowitz from New York, second left, meets with seven of the Scottsboro defendants at the jail in Scottsboro, Ala. just after he asked the governor to pardon the nine youths held in the case. From left are Deputy Sheriff Charles McComb, Leibowitz, and defendants, Roy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Ozie Powell, Willie Robertson, Eugene Williams, Charlie Weems, and Andy Wright. The black youths were charged with an attack on two white women on March 25, 1931. (AP Photo)

n this July 12, 1937 file photo, the eight men due to be arraigned before the Circuit Court in Decatur, Ala. play music at their jail in Birmingham, Ala. before their court appearance. From left are Olen Montgomery, Andy Wright, Eugene Williams, Charlie Weems, Patterson, Clarence Norris (dancing) Roy Wright, Ozie Powell and Willie Roberson, also known as the Scottsboro Boys. They were convicted by all-white juries of raping two white women on a train in Alabama in 1931. All but the youngest were sentenced to death, even though one of the women recanted her story. All eventually got out of prison, but only one received a pardon before he died. (AP Photo)

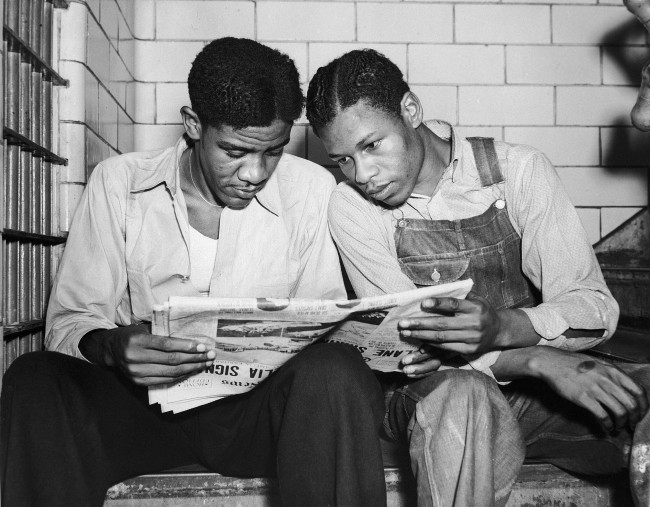

– In this July 16, 1937 file photo, Charlie Weems, left, and Clarence Norris, Scottsboro case defendants, read a newspaper in their Decatur, Ala. jail after Norris was found guilty for a third time by a jury which specified the death penalty. Weems was to be tried a week later.

A throng at Penn Station greeted two of the five Scottsboro boys recently freed, upon arrival in New York July 26, 1937. Officers are shown escorting Olen Montgomery, center, wearing glasses, and Eugene Williams, wearing suspenders, through the crowd. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8658518

Date: 26/07/1937

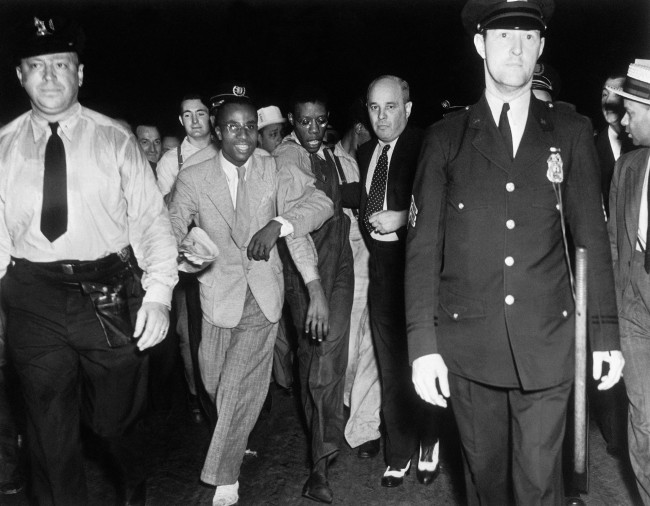

Apparently bewildered by the attention of an uncontrollable crowd, Olen Montgomery is led through Penn Station upon arrival in New York City, July 26, 1937 by his attorney, Sam Liebowitz while an officer marches ahead. (AP Photo).

Ref #: PA.13168414

Date: 26/07/1937

In this July 26, 1937 file photo, police escort two of the five recently freed “Scottsboro Boys,” Olen Montgomery, wearing glasses, third left, and Eugene Williams, wearing suspenders, forth left through the crowd greeting them upon their arrival at Penn Station in New York. In a final chapter to one of the most important civil rights episodes in American history, Alabama lawmakers voted Thursday, April 4, 2013, to give posthumous pardons to the “Scottsboro Boys”: nine black teens who were wrongly convicted of raping two white women in 1931. (AP Photo, File)

In this July 26, 1937 file photo, New York attorney Samuel Leibowitz, center, stands in his office in New York with four of the “Scottsboro Boys,” from left, Willie Robertson, Eugene Williams, Roy Wright, and Olen Montgomery. Levin is credited with saving from death all but one of the nine black teens who were wrongly convicted of raping two white women in 1931. In a final chapter to one of the most important civil rights episodes in American history, Alabama lawmakers voted Thursday, April 4, 2013 to give posthumous pardons to the “Scottsboro Boys”. (AP Photo, File)

Clarence Norris, one of nine blacks involved in the Scottsboro case of 15 years, walks through the main cell gate at Kilby Prison in Montgomery, Ala., Sept. 27, 1946, after receiving his parole after serving nine years of a life sentence. Norris is one of five sentenced to prison in 1937 after six years of court litigation growing out of charges that the nine Scottsboro boys raped a white woman on a freight train. (AP Photo)

Mothers of the Scottsboro, Alabama, black youths condemned to death for an attack on two white women, vent to the White House on Mother’s Day to ask for Presidential intervention. Four of them are pictured with Ruby Bates, one of the women alleged to have been attacked, by the black youths, and Richard B. Moore, black member of the Executive Committee Of The International Labor Defense. Left to Right: Ida Norris, Janie Patterson, Ruby Bates, Mamie Williams, Viola Montgomery , and Moore. A secretary informed the group that it was impossible for the President to receive the group or to intervene. ( AP Photo )

Posted: 10th, December 2014 | In: Key Posts, Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink