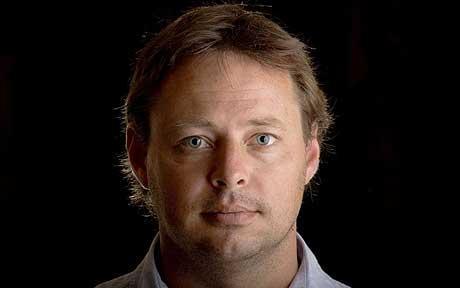

David Hicks’ Guantanamo Memoirs Are Self-Serving, Profiteering And A Cracking Read: Extracts

DAVID Hicks has had his memoirs published in a tome called ‘Guantanamo: My Journey’, published by Random House.

DAVID Hicks has had his memoirs published in a tome called ‘Guantanamo: My Journey’, published by Random House.

Hicks is the Australian who spent five years in Guantanamo Bay, first in the rudimentary Camp X-Ray then in Camp Delta. He was sentenced to seven years jail for “providing material support for terrorism”. Upon release from the Cuban jail he was despatched to Adelaide’s Yatala Prison to serve the remainder of his sentence. In 2007, he was released.

Hicks is able to write his own history. From being a terrorist supporter he appears to be the unlucky victim of circumstance:

What began as an effort to help the Kashmiri cause for independence took a tragic turn when David found himself trapped within Afghanistan as the Northern Alliance bombs began to fall in response to the September 11 attacks. His life in constant danger, David eventually managed to find a safe haven in the house of a shopkeeper, Mustafa, in Kunduz.

His recollections fill 456-pages. Random House has a best seller.

Other highlights are:

“An armed member of the Northern Alliance approached and attempted to engage me in conversation. Not knowing Farsi, I didn’t attempt to answer him. After yelling directly into my ear, he took me by the hand and began to pull me away. I went to resist, but he made a gesture to go for his gun.

“I stole a glance at the young guy I had followed, who was still talking with taxi drivers. He saw what was happening and turned his back, leaving me on my own. With dread, I resigned myself to the situation and allowed myself to be led away. This was the beginning of six years of hell.”

Hicks was sold by the Northern Alliance to the US.

In Guantanamo:

“He entered the cage first, slamming the detainee, pinning him to the cement floor with the shield, while the others beat him in the torso and face.

“The last to enter the cage was a military dog handler with a large German shepherd. The dog was encouraged to bark and growl only centimetres from the Afghani’s face while he was being beaten.”

Later:

“I awoke on a concrete slab with the sun in my face. I looked around and saw that I was in a cage made out of cyclone fencing, the same as the boundary fence around my old primary school. “Internal fences divided the cage into ten enclosures, and I was in one of the corner-end cells. Around me, I saw five other concrete slabs with what looked like birdcages constructed on top. A fence covered in green shadecloth and topped with rolls of razor wire was wrapped around these six concrete slabs, able to house sixty unfortunate human beings. Hanging on the inside of this fence were signs saying, If you attempt escape, you will be shot, complete with a featureless person with a target for a head.

“All around the outside of the shadecloth, civilian and uniformed personnel cleared and flattened grass and trees. They poured cement and assembled the wire cages, calling them blocks. There was nothing much else around us except guard towers boasting large, painted American flags and manned by armed marines.

“My block was only the second to have been built, but that would change over time. As this prison grew out of the grass, more detainees, as they liked to call us, rather than POWs, arrived. About a month later, around three hundred and sixty of us lived in these outdoor enclosures. They were open to the wind, sun, dust and rain and offered no respite. The local wildlife was being disturbed as their homes were bulldozed to make room for the concrete blocks, and scorpions, snakes and nine-inch-long tarantulas tried to find shelter in what were now our enclosures.

“My cage, like all the cages, was three steps wide by three steps long. I shared this space with two small buckets: one to drink out of, the other to use as a toilet. There was an isomat (a five-millimetre-thin foam mat), a towel, a sheet, a bottle of shampoo that smelt like industrial cleaner, a bar of soap (I think), a toothbrush with three-quarters of the handle snapped off and a tube of toothpaste. When I held this tube upside down, even without squeezing, a white, smelly liquid oozed out until it was empty.

“This bizarre operation was called Camp X-Ray. Our plane was the first to arrive on this barren part of the island, and we remained the only detainees for the first three or four days. We had been spaced apart because of the surplus of cages. Every hour of the day and night, we had to produce our wristband for inspection, as well as the end of our toothbrush, in case we had sharpened it into a weapon. These constant disturbances prevented us from sleeping. We were not allowed to talk, or even look around, and had to stare at the concrete between our legs while sitting upright on the ground. If we did lie flat on the concrete, we had to stare at a wooden covering a foot or so above our cages, which served as some type of roof. Apart from blocking the sun for about two hours around high noon, the roof offered no other benefit.

“Sitting or lying in the middle of the cage, away from the sides, were the only two positions we were allowed to assume. We could not stand up unless ordered to, while the biggest sin was to touch the enclosing wire. If we transgressed any of these rules, even if innocently looking about, we were dealt with by the IRF team, an acronym for Instant Reaction Force. The Military Police (MP) nicknamed this procedure being earthed or IRFed, because they would slam and beat us into the ground.

“I first witnessed the IRF team a day or two after my arrival. An MP stopped outside the cage of an Afghani, my closest neighbour at the time. He was the detainee with the prosthetic limb, who had been on the two ships with me. The MP demanded to know what the Afghani had scratched into the cement. He had not scratched anything and could not even speak or understand English. I heard the MP read, Osama will save us. The detainee had no idea what the guard was on about, yet the MP was furious when he did not respond. I’ll teach you to resist, the MP threatened and stormed off. Suddenly six MPs in full riot gear formed a line outside his cage. The first one held a full-length shield. He entered the cage first, slamming the detainee, pinning him to the cement floor with the shield, while the others beat him in the torso and face. The last to enter the cage was a military dog handler with a large German shepherd. The dog was encouraged to bark and growl only centimetres from the Afghani’s face while he was being beaten. In later cases, the dogs bit detainees.

“When they had finished, they chained him up and carried him out. His face was covered in blood. A few hours later an MP washed the blood off the cement with a scrubbing brush and hose. To add to that injustice, an MP told me some weeks later that he himself had scratched that statement into the cement before any of us had arrived at Guantanamo, while they had been training and awaiting our arrival.

“Every two or three days another planeload of detainees would arrive. They were always made to kneel and lean forward on the gravel while being yelled at and struck in the back of the head. They had to balance in this position while one detainee at a time was picked up from the line, escorted into a block and deposited into a cage. Those who were moved first were lucky not to have to endure the stress position for hours. When all the cages in our block had been occupied, detainees began to fill the other newly built blocks around us.

“It was around this time that helicopters hovered above and very large groups of civilians walked through the camp to view us in our cages, specimens in an international makeshift zoo.

“The first two weeks of Camp X-Ray was a blur of hardships: no sleeping, no talking, no moving, no looking, no information. Through a haze of disbelief and fear, pain and confusion, we wondered what was going to happen. To pass time and relieve the pressure on my ailing back, I chose to lie down rather than sit up. During the day I would look slightly to my right, focusing my vision just beyond the wooden roof, and lose myself in the sky beyond. It was an escape, so peaceful, so blue and full of sunlight. I gazed at the odd cloud and spied big, black birds circling high above, called vulture hawks. It was never long, though, before a hostile face blocked the view, screaming, What are you looking at? Look up at the roof. All I could do was sigh and avert my gaze from the infinite, blue sky to a piece of wood.”

Whatever Hicks is or isn’t, the book is a cracking read. It is a guaranteed best seller. But here’s a final word or two on Hicks, again in his own words and written before the memoirs:

So) the Western-Jewish domination is finished, so we live under Muslim law again… Jihad is still valid today and will be for all time. The West is full of poison. The western society is controlled by the Jews with music, TV, houses, cars, free sex takes Muslims away from the true Islam keeps Islam week and in the third world.

On meeting Osama Bin Laden:

By the way I have met Osama bin Laden 20 times now, lovely brother, everything for the cause of Islam. The only reason the west calls him the most wanted Muslim is because he’s got the money to take action

His background is summed up neatly:

Before making it to Afghanistan, he would travel to Pakistan to join the al-Qa’ida-linked terrorist group Lashkar-e-Toiba which sent Willie Brigitte to Australia to commit terrorist atrocities. While in Pakistan he would by his own admission fire what he described as “hundreds of bullets” across the frontier into India. After September 11, 2001, he made his way across the border to Afghanistan.

6702849

Posted: 16th, October 2010 | In: Reviews Comments (3) | TrackBack | Permalink