Rowan Williams Proves He Exists: All Views On Archbishop’s Attack On Coalition

ROWAN Williams say no-one believes in the coalition. There are, after all, no old books to prove its existence. And if one person needed irrefutable proof that something was right and based on truth and hard facts it is the Archbishop of Canterbury.

ROWAN Williams say no-one believes in the coalition. There are, after all, no old books to prove its existence. And if one person needed irrefutable proof that something was right and based on truth and hard facts it is the Archbishop of Canterbury.

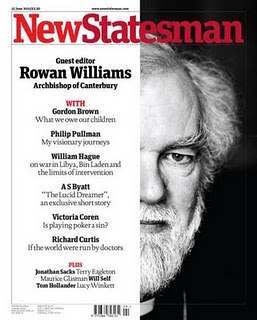

Williams was invited to guest edit the New Statesman.He accepts. In the article headlined: “The government needs to know how afraid people are – We are being committed to radical, long-term policies for which no one voted.”

Fear. Governments and churches thrive on the stuff. Says Williams:

The political debate in the UK at the moment feels pretty stuck. An idea whose roots are firmly in a particular strand of associational socialism has been adopted enthusiastically by the Conservatives. The widespread suspicion that this has been done for opportunistic or money-saving reasons allows many to dismiss what there is of a programme for “big society” initiatives; even the term has fast become painfully stale. But we are still waiting for a full and robust account of what the left would do differently and what a left-inspired version of localism might look like…

Incidentally, this casts some light on the bafflement and indignation that the present government is facing over its proposals for reform in health and education. With remarkable speed, we are being committed to radical, long-term policies for which no one voted. At the very least, there is an understandable anxiety about what democracy means in such a context…

A democracy that would measure up to this sort of ideal – religious in its roots but not exclusive or confessional – would be one in which the central question about any policy would be: how far does it equip a person or group to engage generously and for the long term in building the resourcefulness and well-being of any other person or group, with the state seen as a “community of communities”, to use a phrase popular among syndicalists of an earlier generation?

The thing creates a media fire. Here are the pick of the comments:

On the other hand, this idiot has a point, complaining that the Cleggerons are forcing through “radical policies for which no one voted”. Euroslime Dave and his not so merry men do not have a mandate, neither of the parties represented by the coalition having achieved a majority – with both parties having gone back on pledges made in order to secure their election… So much energy and effort is focused on choosing who elects us – with Blair falling into the trap of believing that this is what matters – while Williams puts his finger on deeper problem. We have a limited control over whom we chose for office but, once in office, we have no control over what they do.

Therein, if I may say so, lies the need for and the justification of Referism. The demos needs to elect its representatives – but that is not enough. Through the span of their office, we need an ongoing mechanism, in order to control them. Relying on politicians’ promises, as we all know, is not good enough, it is too late to vote them out of office after the damage has been done, and the election itself is not that much use when the different parties come up with roughly the same bill of goods.

Daily Mail (front page): BRITAIN’S BISHOPS AT WAR”

Archbishop Nichols praised Mr Cameron for putting marriage and family stability at the centre of policy-making, and he supported his Big Society vision.

His comments appeared to herald a holy war between the liberal-dominated Church of England, increasingly under the sway of clerics who regard state spending as sacrosanct and cuts as immoral, and a Roman Catholic church that backs Mr Cameron’s belief in self-help and the traditional family.

Stephen Glover (Mail):

Would he have insinuated the same thought if there had been a Labour-Lib Dem coalition? I very much doubt it. In fact, the Coalition has more popular support – if you add up the votes of all those who voted Tory and Lib Dem – than any government in modern times.

We all have our limits, and evidently the Archbishop of Canterbury has reached his. Invited to guest-edit this week’s New Statesman, he must have meditated prayerfully and mused long and hard about how he might profess a commitment to left-wing values without being overtly partisan. After all, St Paul’s exhortation was for believers to become all things to all people, and Dr Williams wouldn’t want to blow the chance of ever being asked to guest-edit The Spectator at some point in the future. So, subtlety was the order of the day: wise as serpents and harmless as doves, and all that…

For reasons best known to him, instead of walking the traditional via media, Dr Williams decided to launch a broadside against the Government, essentially describing the coalition as ‘frightening’. He singled out the health, welfare and education reforms which he says constitute ‘radical, long-term policies for which no-one voted’.

As far as His Grace recalls, there was no option to vote ‘Coalition’ on the 2010 general election ballot paper, so, of course, no-one voted for it. But it is crass to assert that the agreed manifesto consists of policies ‘for which no-one voted’. This coalition represents a greater proportion of the electorate and is implementing a broader range of cross-party policies than New Labour ever did: the coalition mandate is broad.

But the Archbishop refers to a democratic deficit which has led to ‘anxiety and anger’ and ‘bafflement and indignation’ due to the ‘remarkable speed’ with which policies are being introduced, and the lack of ‘proper public argument’. On Iain Duncan Smith’s welfare reforms, he complains of a ‘quiet resurgence of the seductive language of “deserving” and “undeserving” poor”’ and criticises ‘the steady pressure’ to increase ‘punitive responses to alleged abuses of the system’.

Well, David Cameron learned from Tony Blair that you can waste years faffing around achieving precisely nothing whilst appearing to be very busy indeed…

The Archbishop is also of the view that the Prime Minister’s flagship policy, the ‘Big Society’, is nothing but a ‘painfully stale’ slogan which is perceived to be an ‘opportunistic’ cover for spending cuts and is viewed with ‘widespread suspicion’. He accepts that it is not a ‘cynical walking-away from the problem’. But he warns there is confusion about how voluntary organisations will pick up the responsibilities shed by government, particularly those related to tackling child poverty, illiteracy, and increasing access to the best schools.

Yet only a few months ago, Dr Williams was delighted with the ‘Big Society’. He distinctly praised its conceptual foundations, in particular the far-reaching possibilities of the development of local co-operation and ‘mutualism’ throughout the entire spectrum of political action. And the Synod firmly embraced the policy when they debated it last year. It is difficult to fathom what has shifted so seismically in just three months (certainly no clarification of what is meant by ‘Big Society’).

But it is curious that Dr Williams never used the adjective ‘frightening’ of New Labour. For the Blairite agenda was far more ‘radical’ than those of the coalition, and the present education reforms have cross-party consensus: indeed, they are the brainchild of Lord Adonis and Tony Blair, who both laud the Gove plan to decentralise and devolve. And it is also strange that Dr Williams says that it is not credible for ministers to blame the last Labour government for Britain’s problems, when he uttered not a word as Blair and Brown spent 13 years blaming Margaret Thatcher for the wrong type of snow. And yet Dr Williams himself refers to the weakening of community and mutualism as a result of ‘several decades of cultural fragmentation’. Perhaps he refers solely to the effects of Thatcherism…

…the Archbishop is simply doing his job: he is braving not just Conservative and LibDem politicians, but the National Secularists and the British Humanists and all who believe that religion should be eradicated from the public sphere. Perhaps buoyed by the visit of Pope Benedict XVI, or spurred on by some of his own bishops, there is no doubt at all that the Established Church has a duty to intervene when it perceives the need. After all, politicians have the constitutional right to interfere in the workings of the Church, and the very presence of the lords spiritual in Parliament presupposes a degree of reciprocity…

While theologians and politicians may argue over the manner of this ‘religious welfare’, especially, it seems, in the provision of benefits, the Archbishop speaks because the Head of State cares and cannot speak. He warns publicly because she may only do so privately. He does not always speak as she would wish to, but by speaking at all he reminds us that there is something which transcends the politicians, who, as Shakespeare observed, have an annoying habit of seeming to see the things they do not…

He may occasionally be a thorn in the side of government. But it is better to have a benign and occasionally misguided Anglican one than a monolithic, absolute and malignant one.

Giles Fraser (Guardian)

Oh no, not this old chestnut again. Should the church get stuck into the mucky world of politics? How ridiculous – of course it should. Dom Hélder Câmara, former Roman Catholic archbishop in Brazil, put it perfectly: “When I give to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.”

The same sentimental doublethink about the church is equally true of how the Tories have responded to the archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams’s suggestion that the coalition government is letting down the most vulnerable in our society. The Tories want religious organisations to play a leading role in the formation of the “big society” (actually, it was our idea in the first place), but then get all uppity when those on the ground start reflecting back to government the effects of their policies – policies that very few of us thought we were voting for.

It is understood Mr Cameron had rejected an offer to contribute to Dr Williams’s edition of the magazine, although Iain Duncan Smith did write a piece.

Mr Cameron said that the Archbishop was free to express his views, but added: “What I would say is that I profoundly disagree with many of the views that he has expressed, particularly on issues like debt and welfare and education.”

The Prime Minister said the Government was acting in a “good and moral” fashion and defended the “Big Society”, and the Coalition’s deficit reduction, welfare and education plans. “I am absolutely convinced that our policies are about actually giving people a greater responsibility and greater chances in their life, and I will defend those very vigorously,” he said.

“By all means let us have a robust debate but I can tell you, it will always be a two-sided debate.”

Tory backbenchers were less restrained. Roger Gale said: “Dr Williams clearly does not understand the democratic process. For him, as an unelected member of the upper house and as an appointed and unelected primate, to criticise the Coalition government as undemocratic and not elected to carry through its programme is unacceptable.”

Don Mackay (Mirror)

ARCHBISHOPS of Canterbury question Government policy – it’s what they do.

Tony Blair yesterday reminded us he was assailed by turbulent priests. Margaret Thatcher faced (in our view, with good reason) ferocious criticism in the 1980s.

So David Cameron should take a chill pill after Dr Rowan Williams voiced concern about the impact of the Coalition on the vulnerable, low paid and communities.

The Archbishop is entitled to express opinions on issues which he believes concern the welfare of his flock. Indeed it would be wrong for him not to do so.

The Prime Minister acknowledged that but his sweeping dismissal of Dr Williams’ comments betrayed his deep irritation.

And Mr Cameron has good reason to be rattled. Because the criticism reflects a growing feeling this regime is inflicting pain and pursuing policies without a mandate.

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s truth hurts David Cameron.

Dr Williams is braced for the counterblast he’s bound to get from the media. But Mr Cameron can afford to be vehement too. He can start by asking for evidence of this public fear the A of C mentions: the polls don’t seem to show it. He can also nail the democratic legitimacy argument, not by asking where Dr W gets his from btw, but by pointing out that the Coalition has a mandate and its policies have been approved by Parliament (and in the case of health the Commons will get to vote again). And he might want to point out the history of close links between the Church and the left, and more recently between Dr Williams and Gordon Brown.

Like any piece of partisan political writing, Dr Williams’s turbulent priest essay plays it sneaky.

Thus, while it is arguable that the Conservatives did not flag up their plans for a huge shake-up of the NHS before the last election (and indeed promised an end to disruptive top-down reorganisations of the health service) it is not fair to say that the party’s school reforms were not exposed to public debate.

The Conservative manifesto from 2010 listed a whole string of changes that the teaching unions hated back then, including new powers for headmasters to pay good teachers more (ie, a break with national pay scales), a focus on more traditional reading methods, more setting and streaming, tougher school inspections, more powers to discipline children, the publication of lots of previously secret performance data about schools, and above all a big expansion of the Academy schools programme creating schools outside local authority control, buttressed by a right for parents and local groups to open their own schools. This was described in the manifesto as a “schools revolution”, explicitly modelled on Sweden’s radical free school model, and American charter schools.

While we are on the subject of sneaky, one of the oldest tricks in the partisan playbook is to caricature your opponents’ arguments before he has a chance to make them. The archbishop does not hesitate to use this ploy. Thus, in one paragraph he asks what he calls some crucial questions that any national government must answer, such as how, at a time of straitened finances, it can continue to address:

…what most would see as root issues: child poverty, poor literacy, the deficit in access to educational excellence, sustainable infrastructure in poorer communities (rural as well as urban), and so on? What is too important to be left to even the most resourceful localism?

Then he adds that bit about the government needing to know how frightened people are, and that:

It isn’t enough to respond with what sounds like a mixture of, “This is the last government’s legacy,” and, “We’d like to do more, but just wait until the economy recovers a bit.”

In case we missed the inference, a New Statesman blog helpfully provides the gloss that this last swipe is “an implicit criticism of The Chancellor, George Osborne”.

This is Mr Osborne dressed up as Aunt Sally, though (an unfortunate vision, sorry). The coalition does talk a lot about the financial mess left by the previous government, it is true. But that is not their one and only response to questions about child poverty, poor literacy or helping more children to enjoy educational excellence. You can disagree or agree with the reforms being proposed by the coalition on this front—Mr Duncan Smith’s universal credit which he hopes will encourage millions back to work by freeing them from the unemployment traps which currently imprison them, the school reforms and so on. But it is plain sneaky to pretend that these policies do not exist, and that the coalition only ever talks about its lack of money.

David Blackburn (The Spectator)

Do the views of the Archbishop of Canterbury matter? Not especially, I would argue, in this secular age. Besides, the archbishop has form when it comes to making ill-judged public statements, which have perhaps damaged his credibility.

Vincent Nichols (Archbishop of Westminster)

…let us take stock of the external environment in the light of our three events so far in deepening social engagement, and what has been said since, particularly by the Prime Minister in an important speech on 23 May about his vision for the Big Society. I was struck by the result of the poll which Edward Stourton conducted at our conference on 6 April in London when he asked all those present whether or not they thought the “Big Society” was a cover for cuts. The overwhelming majority said no. They felt there was a genuine moral agenda here. Furthermore a number of the MPs who were present – in particular some from the Labour Party – also made clear that the moral motivation behind what David Cameron has advocated is something they supported.

Meanwhile, hands up who voted for the Ten Commandments…

Posted: 10th, June 2011 | In: Politicians Comment | TrackBack | Permalink