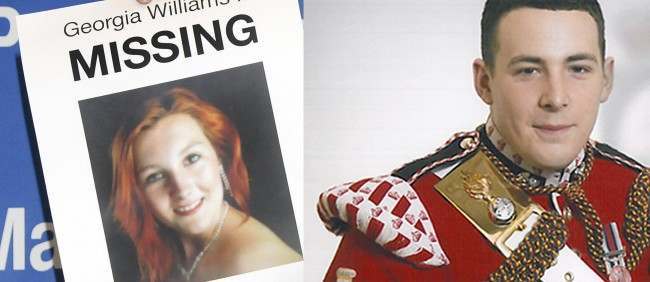

Contempt and the contemptible: Can there be justice for Lee Rigby and Georgia Williams?

FEW people in this country will be unaware of the circumstances in which Drummer Lee Rigby died . The combination of live video, a woman’s confrontation of a suspect at the scene and the unstoppable social media brought the tragedy into every living room.

Many of us will also have been saddened by the disappearance of the teenager Georgia Williams last weekend. A body that is thought to be hers has been found and a young man has been charged with murdering her.

It is in the interests of everyone that whoever perpetrated these crimes is brought to justice.

Armchair criminologists will already see both as open-and-shut cases, yet some will have to serve on the juries that determine whether the men in the dock are guilty – and of what crime.

Contempt laws are in place to try to ensure that anyone accused of a crime has a fair trial – and also that the prosecution is not hampered in holding the guilty to account.

These laws can be frustrating – I remember Harry Evans coming to my local paper in the 70s and declaring the contempt rules to be the biggest official obstruction to British journalism. This is especially so when we look across the Atlantic and see the freedom enjoyed by American reporters. It’s not quite as gung-ho as the musical Chicago would suggest, but the regime is a lot looser than ours.

For the time being, however, we are stuck with the law as it stands, which restricts what can be published once someone has been charged.

MPs have greater freedom than the media as they are protected by parliamentary privilege, and David Cameron used that freedom in his statement to the Commons this afternoon. But how helpful was this to the principles of a fair trial and innocent until proven guilty?

He told MPs that he had set up a task force to find out how ‘the suspects were radicalised and whether anything more could have been done to stop them’. Those who committed ‘this callous and abhorrent crime’, he continued, ‘sought to justiify their actions by extremist ideology’. And in conclusion he described the killing of Drummer Rigby as an horrific murder.

This is a seriously tricky case for politicians and press alike. Two men have been charged with murdering Drummer Rigby under our criminal law. They are not charged with terrorism offences. For the Prime Minister to call them ‘suspects’ offers barely an oakleaf of caution to cover the damning assumptions about their guilt, their motivation and their presumed defence.

Newspapers and broadcasters have been more circumspect, but they all repeatedly say that Drummer Rigby was murdered. You may think he was, I may think he was, but it is for a jury to decide whether he was murdered or the victim of manslaughter or some other crime. It is also noticeable that newspapers that maintain the ‘innocent until convicted or admit a crime’ style of allowing defendants to maintain their honorific are referring to the Woolwich pair by their surnames only.

The same applies to Miss Williams, who is also almost universally described as ‘the murdered teenager’. We don’t know how she met her death – we don’t even know for certain that she is dead – and we have to be careful what and how we report the case so that we don’t influence the course of a young man’s trial.

I was aghast to read this weekend details of Miss Williams’s previous contact with the accused man – and to see his photograph being published. Did the police say identification would not be an issue? Maybe it won’t be. But it’s not for police to make that judgment or for newspapers to accept their word at this stage of proceedings. Background guidance is useful, but we need to pause before we print.

Similarly, going back to Drummer Rigby, papers yesterday and today have reported links between the security services and one of the accused men. This information has doubtless come from ‘informed sources’ within the Establishment, but when it comes to the crunch, it is no more privileged than the word of the last man to lay flowers in Woolwich.

We need to beware of putting too much trust in the ‘terrorism crisis’ lifeboat. There is no guarantee that it is strong enough to see us through this turbulent legal sea and safely to shore. Who wants to see a terrible tangle of appeals through court after court and over to Europe arguing the toss about whether a trial was prejudiced?

Every journalist obviously wants to get as much as possible into his paper or onto her news bulletin. But if we have a responsibility to make sure that innocent people are not convicted and that nasty killers don’t escape justice just because we were incapable of showing a little restraint.

Posted: 4th, June 2013 | In: Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink