The Flying Circus Comes To Town: Monty Python’s Hidden Gems And Forgotten Sadism

The Flying Circus Comes To Town: Python’s hidden gems

THE Flying Circus is back in town, for one last hurrah – or rather a string of them – at London’s O2. The famous old sketches will be enacted again, and the audience will be word-perfect even is the performers aren’t.

The story can be found in a special programme here…

In honour of the reunion, but in the spirit of discovery, we offer a selection of the Pythons’ most obscure back pages….

The album that never was

Monty Python albums weren’t just a way of reliving the sketches in the days before video recorders; they were classics in their own right. Far from being mere cash-ins, they were actually superior to the TV shows, and played a crucial but unsung role in establishing the Monty Python phenomenon.

Back in the day, a generation of schoolboys learned French verbs and poetry by rote, then spent their spare time committing Monty Python sketches to memory in similar dead-parrot fashion, using the tie-in albums and books for homework. Meanwhile in America, where the shows were virtually unknown, the records (on the ‘progressive’ Charisma label) became an integral part of the post-Sixties ‘stoner’ culture. FM djs gave them airplay, and rock stars championed them at every opportunity. They were known as ‘The Pythons’, which sounded like a rock group, and before long they were de facto rock stars themselves, with sell-out live tours and screaming fans. There was even a live album, replete with extra swearing. (The albums were quite risqué, in marked contrast to the strict censorship of the BBC at the time.)

Before singing their praises, it should be acknowledged that the Python albums did have a downside. Firstly, and most shamefully, there was the deathly tradition of ‘doing’ the sketches. Anyone who has stood glassy-eyed during these ritualistic re-enactments will have good reason to curse Charisma Records. And any masochist who hasn’t suffered in this way can experience it vicariously through the ‘romantic comedy’ Sliding Doors, in which John Hannah inexplicably wins the love and admiration of Gwyneth Paltrow by reciting Python at length in a restaurant, to the implausible delight of the assembled company. (Python Fact: Elvis Presley was prone to this sort of thing, and could recite Monty Python and the Holy Grail in its entirety. He was also in the habit of calling members of his Memphis Mafia ‘squire’. And look what happened to him.)

Viewed as a whole, the TV shows are patchy and quite repetitive – understandable, given that they were written and performed in haste, and like all television programmes at the time, were not expected to ‘last’. Anyone watching the first three series for the first time (or watching for the first time since the original screenings) will probably wonder what all the fuss was about. At the time, Python was afforded a certain intellectual importance. Tricksy editing and Terry Gilliam’s distinctive cartoons helped create the impression that it was all very daring and groundbreaking. When sketches ended abruptly with a shooting, or a 100-ton weight falling from the sky, or a camera turning round to show the studio, or credits appearing mid-way through a programme, these tricks were saluted as Brechtian devices or surrealist statements. In reality, they often disguised the lack of proper sketch endings, or were used to simply pad the programmes out. (Indeed, it was the show’s increasingly formulaic nature that prompted Cleese to quit.)

Python also acquired a reputation for controversy, although this had more to do with the broadcasting standards of the times than with any desire to épater le bourgeoisie. Most of the ‘offensive’ material was silly rather than satirical. The transvestite army officers and dummy Princess Margarets were mad rather than bad. Admittedly, the BBC objected to some of the more unsavoury topics, such as masturbation, cannibalism, necrophilia and golf (when the latter was associated with the former). There were also complaints from Mary Whitehouse about the show’s supposed sadism, and later religious controversies over the feature films. All in all, though, it was about as subversive as a Harry Secombe raspberry – and certainly less offensive.

So never mind the series, head straight for the albums. These had several advantages over the shows. Material was cherry-picked, and performed under less hectic conditions, resulting in superior versions of good sketches. Then there was the new material, specially recorded, which was often top-quality. And the format itself allowed the Pythons to play to their strengths. Despite their reputation for ‘surreal’ and ‘zany’ humour, most of the best work relied on verbal inventiveness, which obviously lent itself to the audio medium.

Last but not least, the records allowed the team’s one true genius to flourish. Michael Palin took a keen interest in the recordings, and his performances are a wonder to behold. Matching Tie and Handkerchief is a good starting point, and full of prime Palin cuts. Try First World War, Teleprompter Football Results, or just marvel at the way he says ‘She, sir’ during Cheese Emporium. The Album of the Soundtrack of the Trailer of the Film of Monty Python and the Holy Grail is a great example of an album transcending its origins, and contains a high proportion of sparkling bespoke material. Again Palin shines, never more so than on ‘Marilyn Monroe’, in which he plays a gay- baiting repressed homosexual with unhinged relish.

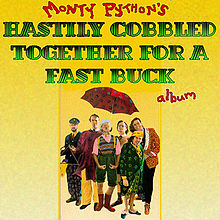

One might think the Python vinyl legacy had been exhausted by the endless barrel-scraping compilations such As Monty Python’s contractual Obligation Album, and yet this isn’t quite true. Another collection, Monty Python’s Hastily Cobbled Together For A Fast Buck Album, was assembled but never released.

However, Michael Palin gave a copies to the road crew of Motörhead, who were fans. Indeed, there is even a sketch included which discusses the band’s music. Bootlegs inevitably emerged, and they include some excellent material, such as Headmaster / Dead Schoolboy. The complete album can be heard here.

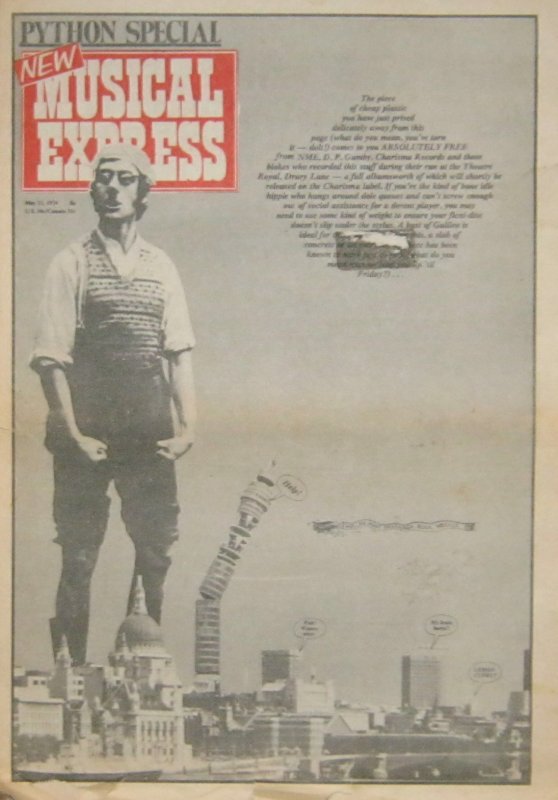

The long-forgotten single

From the heyday of the flexi-disc when the likes of Slade and even the Roling Stones would record special tracks and messages for bendy records that were glued to the covers of magazines, came Monty Python’s Tiny Black Round Thing, courtesy of the NME.

Released to promote their first live album, the single features samples of same, plus several minutes of pure Palin, extemporising on the absorbent qualities of the New Musical Express, and the hygienic reliability of Alf’s Café in Russell Street…

Long-forgotten, although NME was selling about a quarter of a million copies at the time, thus ensuring it ‘sold’ considerably better than any of the Pythons’ official 45rpm releases.

Nice little earners

Some genuine eye-openers here, as the Circus made themselves available as guns for hire at weddings, bah mitzvahs, adverts, corporate films and awards ceremonies…

Best obscure sketch

This one for Dutch TV, is pretty rare. (NB: Younger viewers may not know that Asa Hartford was a famous Scottish footballer.)

In 1972 the Pythons broadcast two 45-minute episodes in Germany, billed as Monty Python’s Fliegender Zirkus. Both programmes were specially created and included new material that was never used in British shows.

Some of the new material, such as The Tale of Happy Valley, was only available in the second Python Book, The Brand New Monty Python Bok.

The highlight, though, was the hearing aid sketch,

This beautifully constructed farce bore all the hallmarks of classic 1960s comedy. Which is unsurprising, because that’s exactly what it was, as can be seen here at 1.10…

That clip is from At Last The 1948 Show, in which John Cleese and Graham Chapman (already established as scriptwriters for a variety of TV comedy shows) performed alongside Tim Brooke-Taylor and the great Marty Feldman. Python sketches such as the Four Yorkshiremen

And the Bookshop Sketch, a forerunner of the Cheese Shop, this time with the customer as timewaster.

And the blueprint for Palin’s loony vicar…

The forgotten forerunner:

While Cleese and Chapman were earning a grown-up living, Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Eric Idle were busy creating the best children’s programme of all time, Do Not Adjust Your Set.

The forgotten sequel

Jones and Palin’s Ripping Yarns is rightly remembered as a comic classic. (Well, parts of it, anyway.) Fawlty Towers is of course comedy royalty, but Cleese also found time to go back to his mainstream roots by writing and performing with Les Dawson…

But you don’t hear much about Eric Idle’s shoestring production, Rutland Weekend Television:

Apart, that is, from its monster bastard offspring, The Rutles:

Which is a shame, because, it had its moments. Here, as a taster, is the first episode. As you can imagine..

And finally, the oddest ‘extra’

Today, Michael Palin is a mainstream celebrity, known primarily for his fantastically successful travel documentaries. Looking at him now, it is surprising to recall that in his Python heyday, his performances were frequently manic and dangerous.

One of Palin’s strangest performances is a short sketch for the reissued Holy Grail DVD. It’s a spoof government information film about the correct use of coconuts, and Palin plays the kind of pinstriped functionary that he habitually sent up as a young man. Yet now he is the same age as the character he is playing, and he performs the role dead straight. It’s funny (of course) but also disconcerting and strangely poignant. It put me in mind of an observation by one of the Pythons, who said that their comedy was a way of lampooning the kind of people they would otherwise have become. In retrospect it is easy to see Palin’s gentle nature projected on to the meek civil servants, accountants and vicars that he often plays.

Posted: 2nd, July 2014 | In: Celebrities, Key Posts, TV & Radio Comment | TrackBack | Permalink