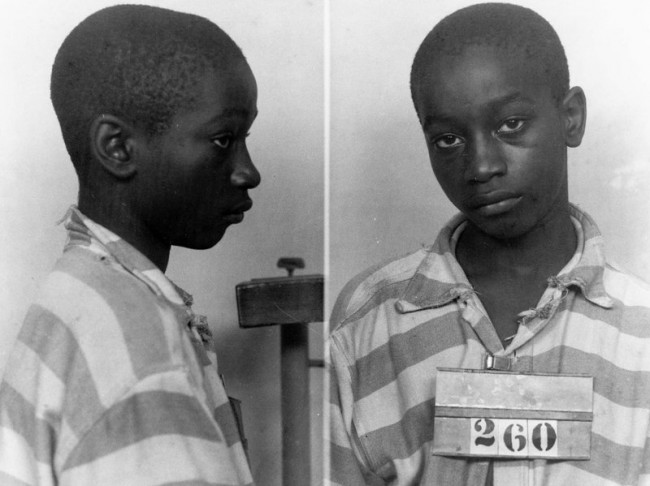

The trial and execution of 14-year-old George Stinney

George Stinney was 14 when he was executed in the electric chair. An all-white jury had found him guilty of killing two white girls, Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8, in the spring of 1944. George Stinney was black.

The victims and Stinney lived in the segregated mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina.

In this Dec. 5, 1939 file photo, President Franklin Roosevelt, left, talks to South Carolina Governor Olin Johnston at a breakfast in the mansion at Columbia, S.C. Leaving a judge to decide whether to throw out the conviction of 14-year-old George Stinney, who was executed in South Carolina in 1944, reminds his supporters of how the teen’s fate was also in Johnston’s hands nearly 70 years ago. Stinney’s conviction is being challenged by a lawsuit filed by supporters asking for a new trial, a move unprecedented in South Carolina for someone already put to death. A hearing has been scheduled for Jan. 21, 2014. (AP File Photo)

The jury took three hours to find him guilty.

He had been removed from all family and friends and kept in prison. The authoriteis said he had confessed.

He was questioned in a small room, alone – without his parents, without an attorney. (Gideon v. Wainwright, the landmark Supreme Court case guaranteeing the right to counsel, wouldn’t be decided until 1963.) Police claimed the boy confessed to killing Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8, admitting he wanted to have sex with Betty. They rushed him to trial. After a few hours of testimony and 10 minutes of deliberation, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to die by electrocution – “until your body be dead in accordance with law. And may God have mercy on your soul,” court documents said. His court-appointed attorney never sought an appeal.

(The US abolished executions of children under 18 in 2005.)

George Stinney’s second cousin Irene Lawson-Hill, center, tells a crowd her family won’t stop fighting, at a rally to call for justice for George Stinney on Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2013, in Manning, S.C. Stinney was 14 in 1944 when South Carolina executed him for killing two white girls. Supporters say there is no evidence against Stinney. (AP Photo/Jeffrey Collins)

But he wasn’t guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

James Gamble, whose father was the sheriff at the time, told the Herald in 2003 he was in the back seat with Stinney when his father drove the boy to prison.

“There wasn’t ever any doubt about him being guilty,” he said. “He was real talkative about it. He said, ‘I’m real sorry. I didn’t want to kill them girls.’ “

Indeed, just 84 days after the girls’ deaths, Stinney was sent to the electric chair. Today, an appeal from a death sentence is all but automatic, and years, even decades, pass before an execution, which provides at least some time for new evidence to emerge.

Betty June Binnicker

Attempts to overturn the conviction have met with resistance among Alcolu’s white community. Sadie Duke told the local paper in January 2014 that the day before the murders, George had told her and a friend: “If you don’t get away from here and if you ever come back, I will kill you.” Another local, who was 15 at the time, said George was known as a bully.

Asked whether she recognised this version of her brother, Aime says: “The only white kids that came in our area was those kids. We had our own black school and church. We didn’t fool around with white people.” Members of Alcolu’s black community say that it was unlikely that, in the segregated town, any black child would threaten white children without there being repercussions.

However, back in 1995, WL Hamilton, George’s seventh grade teacher, who is black, told the Item newspaper that he had a temper and had got into a fight with a girl at school, scratching her with a knife. Aime said she phoned Hamilton after she read the story. “That bastard. That was a damn lie. When I heard about that lie Mr Hamilton told I called him up. I said my name is Aime Stinney and you said my brother was a bad boy. You’ve got one foot on a banana peel and the other going straight to hell.”

Betty June Binnicker’s family never moved too far from Alcolu. A few weeks ago Frankie Bailey Dyches, Betty June’s niece, helped organise a gathering of family and acquaintances to counter what she said was a false impression of George Stinney. In a restaurant outside Manning, less than five miles away, Frankie and her cousin Carolyn Geddings talk about the case over the detritus of a southern lunch of fried chicken, prime ribs, rice and gravy. Dyches and Geddings, both 62, have grown up with the grief of their mothers, Betty June’s elder sisters, and their grandparents Daisy and John Binnicker. To them, George’s confession, and a handwritten note from a Clarendon County deputy stating he confessed and had led them to the murder weapon – a 15in railroad spike – was proof enough of his guilt.

“It seems like a poor little black boy was railroaded by the white people, but that’s not how it was,” said Dyches. “I’m 100% convinced he did it.” One of the investigating officers, Mr Pratt, had told her before he died never to doubt George’s guilt.

“The stories we hear are that he was a shy bashful boy, but he was a bully and he was mean,” she said, citing allegations by Duke and others. She questions the memories of the Stinney family, the motivation of the attorneys and the timing of the appeal. “Why now? What about in the 1960s, when the civil rights movement was starting? What about in the 1970s or 80s? One was a school teacher. It’s not as though they weren’t educated.”

Now Carmen Mullen said the case was a great injustice.

….70 years after he became the youngest person executed in the U.S. in the 1900s. A judge ruled he was denied due process.

“I think it’s long overdue,” Stinney’s sister, Katherine Stinney Robinson, 80, tells local newspaper The Manning Times. “I’m just thrilled because it’s overdue.”

In her ruling, Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen wrote that she found that “fundamental, Constitutional violations of due process exist in the 1944 prosecution of George Stinney, Jr., and hereby vacates the judgment.”

The case was brought by Stinney Robinson and two of her surviving siblings…

George Stinney Jr. was executed less than three months after the two girls were murdered. His trial lasted just one day. After the jury needed less than 10 minutes to declare him guilty, no appeals were filed on his behalf.

“His executioners noted the electric chair straps didn’t fit him, and an electrode was too big for his leg,” The State newspaper reports. The paper adds, “It took Mullen nearly four times as long to issue her ruling as it took in 1944 to go from arrest to execution.”

Justice moves slowly when you’re powerless….

Posted: 18th, December 2014 | In: Reviews 0 Comments | TrackBack | Permalink