Internet journalist don’t need a union to tell them George Bush had a plastic turkey for Thanksgiving

Anorak has employed journalists for over 15 years. And not one – not one – has been a union member. Why not? The Washington Post’s Lydia DePillis knows:

There are two fundamental forces at work here: One is the loss of leverage, with more aspiring journalists than there are jobs and an environment in which content is becoming increasingly commoditized. The other is a shift in identity, with a generation of younger workers less familiar with unions who’ve built personal brands that they can transfer to other media companies.

But those other media companies don’t pay all that well. And they are desperate. The Daily Telegraph, for instance, used to be a venerable institution. It’s not any longer. These are, at the time of writing, the ‘Most Viewed’ stories on the Telegraph‘s website:

Does any budding journalist still dream of writing for the Telegraph?

You no longer need specialists; you just need writers who can get traffic.

Take football reporting. It’s now all such utter balls. Anorak’s Transfer Balls column tracks the to-deadline ‘exclusives’ that keep readers clicking. One newspaper reports a rumour as fact. The other newspapers copy and paste it. Everyone is in the same space. And anyone with a keyboard can do it.

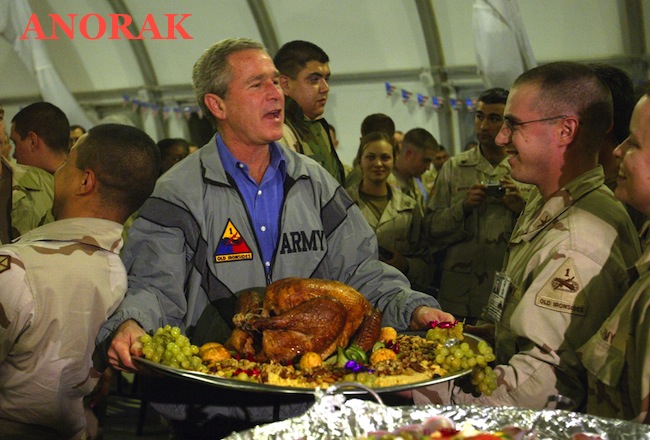

What goes for football, also goes for scoops about three-breasted women and Gorge Bush’s plastic turkey. One news source says it. The panicky rivals race to copy, paste and publish it.

The Sun: “Woman with 3 breasts eats Arsenal football club!”

The Mirror: “Woman with three breasts eats Arsenal football club?”

The Times: “Woman with three breasts eats Arsenal football club, sources say”

The Guardian: “Woman with three breasts eats Arsenal football club – live blog!”

DePillis adds:

The other phenomenon, of course, is that Web writing has become commoditized. Not only are there hordes of recent graduates who would gladly fill holes on a masthead, new media organizations don’t necessarily need large newsrooms of reporters; cheap freelancers and Web editors to repackage other articles are abundant. In part, that’s how places like Gawker and Forbes.com have thrived. When the Newspaper Guild tried to organize a boycott of the Huffington Post for refusing to pay its thousands of bloggers, even progressive contributors crossed the picket line. The Huffington Post didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Not paying your writers is an awful move. If it’s good enough to feature, it’s good enough to pay for.

Choire Sicha also knows:

“If you look at the big ones, like BuzzFeed or Vox, the young workers are in general SO homogenous, and SO unprepared for anything like union organizing. They all went to good schools, and very few of them seem to have any experience with labor in the real workforce. And they’re all young and haven’t started worrying about their future yet. (Surprise: they don’t really have one!)”

There is a lot of great talent out there. The problem is how to afford it? Advertisers and marketing is calling the shots. Newspaper are looking a lot like infomercials. The money dictates the policy.

Andrew Sullivan writes:

…one particular form of journalism is actually dying because of this technological shift – and it’s magazines, not blogs. When every page in a magazine can be detached from the others, when readers rarely absorb a coherent assemblage of writers in a bound paper publication, but pick and choose whom to read online where individual stories and posts overwhelm any single collective form of content, the magazine as we have long known it is effectively over.

Without paper and staples, it doesn’t fall apart so much as explodes into many pieces hurtling into the broader web. Where these pieces come from doesn’t matter much to the reader. So what’s taking the place of magazines are blog-hubs or group-blogs with more links, bigger and bigger ambitions and lower costs. Or aggregated bloggers/writers/galley slave curators designed by “magazines” to be sold in themed chunks. That’s why the Atlantic.com began as a collection of bloggers and swiftly turned them all into chopped up advertizing-geared “channels.” That form of online magazine has nothing to do with its writing as such or its writers; it’s a way to use writers to procure money from corporations. And those channels now include direct corporate-written ad copy, designed to look as much like the actual “magazine” as modesty allows.

Magazines in their great age, before they were unmoored from their spines and digitally picked apart, before perpetual blogging made them permeable packages, changing mood at every hour and up all night like colicky infants—magazines were expected to be magisterial registers of the passing scene. Yet, though they were in principle temporal, a few became dateless, timeless. The proof of this condition was that they piled up, remorselessly, in garages and basements, to be read . . . later.

Posted: 1st, February 2015 | In: Key Posts, Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink