Gordon Anglesea: protected, persecuted and finally prosecuted

Gordon Anglesea was a top copper in north Wales when he was molesting children. Today he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for his abhorrent crimes.

Gordon Anglesea is 79.

He was convicted of one charge of indecent assault against one boy, and three indecent assaults against another. His offences took place between 1982 and 1987, when both boys were aged 14 or 15.

Judge Geraint Walters said Anglesea was “beyond reproach”.

The BBC delivers a timeline of the conniving copper:

1967 – Anglesea starts work as a police officer in Cheshire. He later resigned following a marriage breakdown and joined Flintshire constabulary.

1976 – Promoted to inspector in Wrexham and in 1978, becomes responsible for the Bromfield area which included the Bryn Estyn children’s home

1978 – Sets up a Home Office attendance centre in Wrexham

1988 – Becomes a superintendent in Colwyn Bay

And then:

1991 – Retires suddenly after 34 years’ service. Later that year the Independent On Sunday runs an article about Anglesea’s connections with Bryn Estyn. Similar stories follow in the Observer, Private Eye and on HTV Wales.

He said he was libelled. Anglesea said he had never molested boys when working as uniformed police inspector. The courts agreed. But he was lying.

1994 – Sues the four media organisations for libel and is awarded £375,000 in damages

1997 – Answers questions about allegations of sexual abuse before the north Wales child abuse tribunal.

2000 – The Waterhouse report says the allegations about Anglesea had not been “proved to our satisfaction”

The Times reported on February 16, 2000:

Widespread sexual abuse of boys and girls occurred in children’s residential homes in North Wales between 1974 and 1990, according to the Waterhouse tribunal’s report, Lost In Care.

It found that a paedophile ring did exist in the Wrexham and Chester areas, consisting of adult men targeting boys in their mid-teens. Youngsters in care were particularly vulnerable to their approaches.

The tribunal was appointed in 1996 by William Hague, who was then Welsh Secretary, after Clwyd County Council decided against publishing a report by a social services expert, John Jillings, into abuse of children in care. The council feared that it would be sued for defamation; it was also warned against publication by its insurers because of the possible effect of compensation claims.

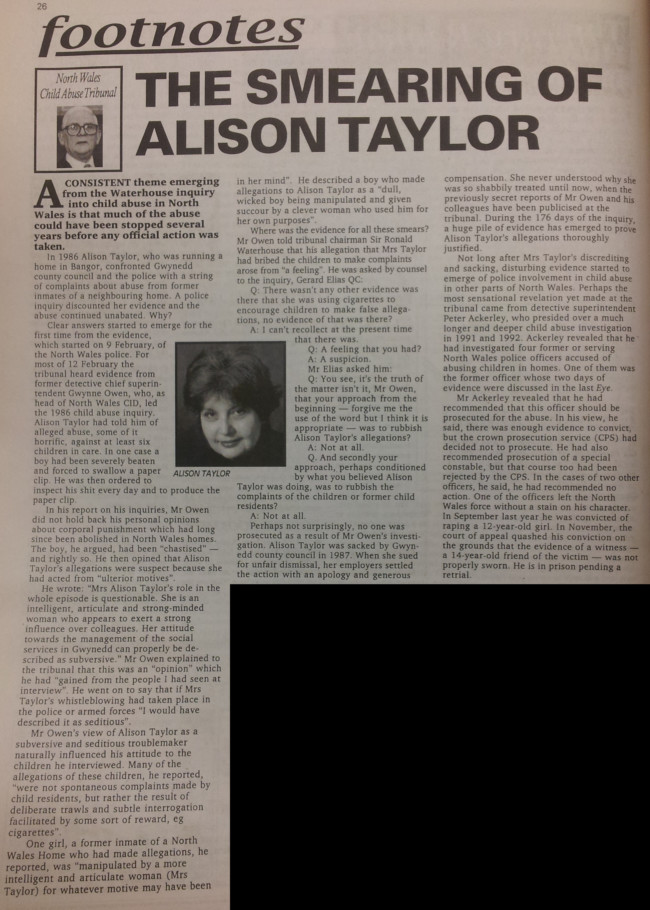

Although by 1996 12 people in North Wales had been convicted of abusing children, there was speculation that the abuse was on a much greater scale. In 1986, Alison Taylor, officer-in-charge of Ty Newydd local authority children’s home in Bangor, had complained to her superiors in Gwynedd County Council about alleged assaults on children. Dissatisfied with the response, she spoke to Keith Marshall, a county councillor, who reported her concerns to the Chief Constable of North Wales.

A police investigation was carried out by Detective Chief Superintendent Gwynne Owen, head of North Wales CID, from 1986 to 1988. The Crown Prosecution Service recommended no criminal proceedings. The investigation is described in the report as defective, sluggish and shallow.

Eric Davies, chairman of Clwyd social services, wrote a memorandum about Ms Taylor saying: “She is a blatant troublemaker, with a most devious personality … I would very humbly suggest … that this lady’s services be dispensed with at the earliest possible time.” Ms Taylor was suspended and eventually accepted voluntary redundancy.

However, she contacted the Prime Minister, Welsh Office, Health Secretary and Local Government Ombudsman. She compiled a voluminous document that was presented to the new social services chairman, Malcolm King, in 1991. He reported it to the police.

The report states that without Alison Taylor’s complaints, there would have been no public inquiry into the alleged abuse of children in Gwynedd. In general terms, she has been vindicated. The response by senior management at Gwynedd County Council to her complaints was discouraging and inappropriate. The Welsh Office’s response was inadequate.

The ensuing North Wales Police investigation, from 1991-93, took statements from more than 500 former children’s home residents who complained of abuse. Some of the most chilling came from beyond the grave. At least 12 children formerly in care have died, most by their own hand. Statements made by six, who died after telling police in the early 1990s about abuse and brutality in the Bryn Estyn community home in Wrexham, were read to the inquiry.

As the police investigation continued, newspaper articles, beginning with the Independent on Sunday, linked a former police superintendent, Gordon Anglesea, to child sexual abuse. He successfully sued for libel, receiving damages of Pounds 375,000, in 1994. The tribunal heard evidence alleging that Mr Anglesea did commit serious sexual misconduct at Bryn Estyn, but were not persuaded that the libel jury’s verdict was wrong.

The report details the abuse experienced by children from the 1970s and names some of the perpetrators. At the local authority-run Bryn Estyn, senior officers Peter Howarth and Stephen Norris sexually assaulted and buggered many boys. Norris continued to abuse boys as officer-in-charge of another home, Cartrefle, until he was arrested.

Alison Taylor, as described by the Guardian in 1998:

In North Wales, it was Alison Taylor, the manager of a children’s home, who spent five years banging on the door of her employers at Gwynedd Council, the police, the Welsh Office, the Department of Health, and the Social Services Inspectorate. All turned her away. Undaunted, she compiled a dossier of 75 separate allegations, won the backing of two local councillors and finally secured the conviction of four men for an orgy of abuse. As a result, the Government finally ordered the vast public inquiry which has now heard nearly 300 former residents of homes make detailed complaints of physical and sexual assault against148 adults. By that time, however, Alison Taylor had been suspended and sacked.

Private Eye, 20th February 1998 by Paul Foot (via)

Time rolled on.

2014 – Arrested and bailed by officers from Operation Pallial, an investigation into child abuse in north Wales care homes

2015 – Charged with historical sex offences

2016 – GORDON ANGLESEA IS JAILED.

Anglesea was investigated as part of Operation Pallial. As a results, 8 men have been convicted, including care home owner John Allen, who was jailed for life in 2014.

John Allen was 73 when he was jailed.

Old men get it in the neck after years of getting away with it.

Former hotelier Allen opened his first home, Bryn Alyn Hall in Llay, near Wrexham, in 1968, although he did not have any qualifications in childcare, his trial was told.

He set up the Bryn Alyn Community, which was to become one of the UK’s largest providers of residential care, providing accommodation for children sent from about a dozen local authorities.During the trial, which began in early October, the jury was told of Allen’s previous conviction in 1995 for six counts of indecent assault involving repeated abuse of six boys dating from the 1970s.

More victims came forward following the publication of the Waterhouse report into abuse in north Wales care homes in 2001 and after Operation Pallial was set up.

One former resident at the Bryn Alyn children’s home said living there “wasn’t care, it was like hell”.

Denial and despair in North Wales (September 1997), The Guardian, September 1997, by Nick Davies:

Without power to resist, the children were utterly vulnerable to the paedophiles who had infiltrated the homes. They became sex objects – in the dormitory and in the sick bay, in Peter Howarth’s flat and in Stephen Norris’ room, in the showers, in the staff room, in the bath, in cars, in sheds, in tents, on the tow path of a canal; with men, with women, with residential workers, social workers and with anyone else who wanted them because on the evidence of these survivors, in these children’s homes, no paedophile ever failed to get his or her way…

For the adults, this was a world without boundaries: a woman worker saw a good-looking 14-year-old boy so she screwed him; a man saw a 12-year-old girl who was pretty so he pulled her into a shed and raped her. One boy was allegedly being used for sex by both his housemaster and the female deputy housemaster. When a teacher complained about this, and took the boy home to protect him, his superiors alleged that he, too, was abusing the child. The teacher protested his innocence, explaining that it was his wife and not he who had also started having sex with the boy.

…

Many simply buckled and did everything they could to comply, searching for favour from their tormentors. One man described how he had been anally raped with such violence that his backside had bled for days. He was afraid that someone would be cross with him for having blood on his underpants and so, several times, he had secretly taken them and flushed them down the loo.

…

Two girls ran away and were picked up by police who told them they were lying about conditions in the home. Once the police had left them, one of the women recalled, a care worker punched her in the stomach while her friend was taken into a side room, from which she emerged later with a bruised eye and a split lip. On at least 12 occasions, over the years, police were asked to investigate allegations of violence or paedophilia in the homes but, almost always, their inquiries came to nothing.

Who knew about Anglesea? And why did it take so long for Officer Anglesea to face justice?

Posted: 4th, November 2016 | In: Key Posts, Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink