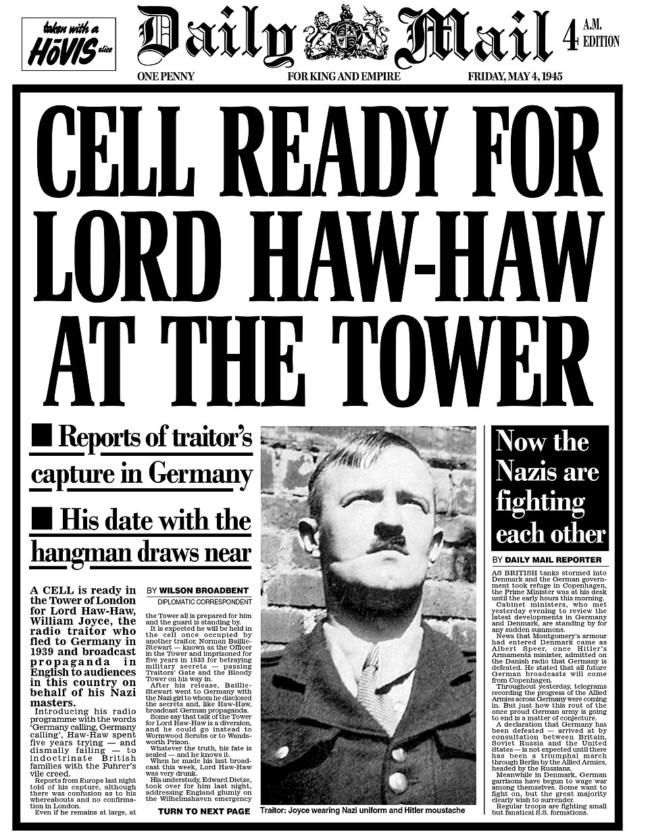

The death of Lord Haw-Haw

On this day 1946, William Brooke Joyce (24 April 1906 – 3 January 1946) was hanged. Lord Haw-Haw, as he was known, was the last person to be executed for treason in the United Kingdom.

On the cold and damp morning of 3 January 1946, a large but orderly crowd had formed outside the grim Victorian prison in Wandsworth, the main gates of which aren’t more than a stone’s throw from the more salubrious surroundings of Wandsworth Common in south London. Some people had come to protest at what they considered an unjust conviction; others, albeit a handful, came to demonstrate about the use of capital punishment; while some, rather morbidly, wanted to be as close as they could to what came to be the last execution of a person convicted of high treason in Britain.

About 500 miles away, as the crow flies, at Joyce’s old school called St Ignatius, in Galway, a mass was taking place. The consecration of the Eucharist was timed for exactly the moment that Joyce was due to be executed. In the end the planned timing was in vain. It was at one minute to nine, an hour later than initially planned, when the governor of Wandsworth prison entered the condemned man’s cell to inform him that his time had come.

William Joyce had woken early that morning. He washed, but didn’t shave, and changed from his prison clothes into the blue serge suit he had been wearing at the time of his arrest in Germany. He refused any breakfast but he drank a cup of tea. For the last few months Joyce had actually been eating relatively well and while in prison his weight had increased substantially. When he was first brought to Wandsworth in the autumn he weighed 135 pounds (61 kg) but was now 151 pounds (68.5 kg). This wasn’t incidental information at the time; the weight gain was of more than passing interest to Albert Pierrepoint, the man who was to be his executioner.

The weight of every prisoner for whose death he would be ultimately responsible, he carefully noted in a leather-covered diary or ledger. It carried the details of all the executions for which he had been responsible and contained the dates, ages, heights, weights and, most importantly, the ‘drop’ for each hanging. Part of the hangman’s craft was to calculate the exact length of rope required to instantly kill the condemned man or woman. If the rope was too long, the criminal would be decapitated; too short, and it would be an agonising death of several minutes by strangulation.

Pierrepoint’s calculations were worked out from grim advice given in an official 1913 government document called the Table of Drops. It had been put together after a series of failed hangings at the end of the nineteenth century, including those of John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee, also known, not surprisingly, as ‘the man they couldn’t hang’. Lee survived three attempts to hang him at Exeter Prison in 1885 after which the Home Secretary commuted his death sentence. He was released twenty-two years later in 1905 and died in the USA in 1945. A committee, chaired by Lord Aberdare, was formed in 1886 to discover and report on the most effective manner of hanging, the results of which were published three years later. After a few more unfortunate incidents, a significantly revised edition of the Table of Drops was published in 1913.

In 1917, as a twelve-year-old, and twenty-eight years before he came face to face with William Joyce in the cell at Wandsworth, Albert Pierrepoint had been asked at school to compose an essay about his future ambitions. He wrote: ‘I would like to be public executioner as my Dad is, because it needs a steady man who is good with his hands like my Dad and my Uncle Tom and I shall be the same.’ Young Albert had only found out about his father’s macabre profession the year before, although he didn’t know that, after carrying out 107 executions, he had been dismissed from his post seven years previously after arriving drunk at Chelmsford prison to carry out a hanging. Albert’s Uncle Tom, however, went on to work as a hangman for thirty-seven years before his eventual retirement in 1946 after a dispute over compensation for a cancelled hanging.

When Albert Pierrepoint met Lord Haw-Haw, Albeit Rather Briefly – Flashbak – and Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics by Rob Baker

Posted: 3rd, January 2019 | In: Key Posts, News 1 Comment | TrackBack | Permalink