David Dimbleby and why the Posh live in a meritocracy

Are you posh? I’m asking for David Dimbleby, the hereditary BBC journalist, former Bullingdon Club member, pal to Prince Charles and whose son attended Eton College. His fellow BBC lifer John Humphrys asked Dimbers if he was a posho. Dimbleby thought the question not rhetorical and replied: “I come from Wales, as you do.” So he is Posh, then, at least as privileged as his nation’s prince. Of course, what Dimbleby’s doing is denying his poshness. The old sod pitches himself as an outsider, a man of the valleys and so very unlike those entitled and titled toffs in Berkshire (Thatcham) and London (Newham).

Kenan Malik cites Dimbleby’s egotism – that stated belief in success founded on merit rather than dumb luck and membership of an elite tribe – in his article on the rise of meritocracy and those who can afford to live in one. Dimbleby is the product of talent and hard work. His rank played no role. Now read on:

So entrenched as a social aspiration has meritocracy become that we often forget that the term was coined in mockery. In his 1958 satire, The Rise of Meritocracy, the sociologist Michael Young told of a society in which classes were sorted not by the hereditary principle but by the formula IQ + Effort = Merit.

In this new society, “the eminent know that success is a just reward for their own capacity”, while the lower orders deserve their fate. Having been tested again and again and “labelled ‘dunce’ repeatedly”, they have no choice but “to recognise that they have an inferior status”.

Young’s dystopian meritocracy doesn’t (yet) exist, but we have something perhaps worse: the pretence of a meritocracy. The pretence that talent will achieve its just rewards in a society in which class distinctions continue to shape educational outcomes, job prospects, income and health.

Malik argues that rank is now based on education. Is admission to top colleges a meritocratic process? It’s competitive. How do you get the edge? How do you know where the edge exists if you’ve no access to it?

Today, we simultaneously deride poshness and want to be seen as having the common touch (hence Dimbleby’s outrage at being called posh), while also showing contempt for those who are deemed too common and whose commonness exhibits itself in the refusal to accept the wisdom of expertise and in being in possession of the wrong social values.

Trump supporters, wrote David Rothkopf, professor of international relations, former CEO of Foreign Policy magazine and a member of Bill Clinton’s administration, are people “threatened by what they don’t understand and what they don’t understand is almost everything”. They regard knowledge as “not a useful tool but a cunning barrier elites have created to keep power from the average man and woman”. Much the same has been said about Brexit supporters…

Too true, of course. Tory MP Michael Gove says a second Brexit referendum would tell voters that they’re “too thick” to decide on issues. Labour MP Mr Sheerman, opined: “The truth is that when you look at who voted to Remain, most of them were the better educated people in our country.”

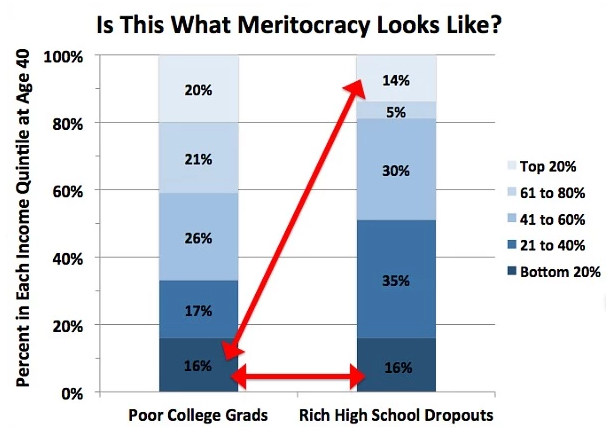

Matt O’Brien finds evidence that “poor kids who do everything right don’t do much better than rich kids who do everything wrong”:

You can see that in the above chart, based on a new paper from Richard Reeves and Isabel Sawhill, presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s annual conference, which is underway. Specifically, rich high school dropouts remain in the top about as much as poor college grads stay stuck in the bottom — 14 versus 16 percent, respectively. Not only that, but these low-income strivers are just as likely to end up in the bottom as these wealthy ne’er-do-wells. Some meritocracy.

What’s going on?

Well, it’s all about glass floors and glass ceilings. Rich kids who can go work for the family business — and, in Canada at least, 70 percent of the sons of the top 1 percent do just that — or inherit the family estate don’t need a high school diploma to get ahead. It’s an extreme example of what economists call “opportunity hoarding.” That includes everything from legacy college admissions to unpaid internships that let affluent parents rig the game a little more in their children’s favor.

David Dimbleby’s dad worked at the BBC, where he hosted the long-running current affairs programme Panorama. David succeeded his father as presenter of Panorama in 1974. Maybe knowledge and know how is inherited, like cash and connections?

Posted: 30th, December 2018 | In: Key Posts, Money, News, Politicians Comment | TrackBack | Permalink